If you have ten minutes to spare, go check out my recent contribution to Oslo University (TF)’s “Luther Blog.” You can find it by clicking HERE.

The Texts We Turned Into Weapons

Imagine writing a text. The slow process, the everyday banality suddenly crafted into beautifully penned narratives. Imagine reading and re-reading the final product, gripping it firmly in your hands while your heart swells with a sweet pride. Now imagine that 300 years after you wrote your text, your proud grip has been replaced by the bloody hands of persecutors using the words you wrote to justify murder.

When the author of the Matthean Gospel wrote that the Scribes and Pharisees were whitewashed tombs, could he (let’s be honest, the author was statistically most probably male) ever have imagined that those words would be used to validate the systematic persecution of his own people (yes, I am assuming that the Matthean author was Jewish, there is lots of scholarly literature in favour of this, look it up). Post-Constantinian Christianity turned the Gospel authors into persecutors. They read the narratives, the parables, and the miracle stories and saw in them the legitimacy they needed for their colonial oppression of the Jews. Imagine that someone discovers your writings 300 years after your death, and sees in your words the justification for a systematic terrorization of your own people. The tragedy is overwhelming.

When I get criticised for reading New Testament texts as Jewish texts, this is what I think about. The overwhelming tragedy that was caused by Christians not understanding that these texts were written by Jews, not against Jews. Scholars who are part of what is sometimes called the ‘radical movement’ (if reading texts in their proper historical context is considered radical, then so be it) are occasionally referred to as “Post-World-War-II-Scholars”. My question is this: would you want to be a “Pre-World-War-II-Scholar?” It is impossible to ignore the terrifying fact that certain aspects of the NT exegesis of the 1900’s played a part in the success of Hitler’s hate campaign. If the systematic murder of European Jews isn’t enough to make exegetes change their stubborn strategies, what is? Academia cannot be so disconnected from the events of history that it doesn’t react or respond to the disasters it contributes to. We are part of the constant ebb and flow of reality; we are not above it. We are subject to the tide of history in the same way as everyone else, and if we choose to not react or respond, the fault lies with us.

We live in a Post-WWII world, and we need to be constantly aware of this in our scholarship. We work in a field that was both misused and actively contributed to one of the greatest disasters of the modern era. The Holocaust would not have been possible if Christian texts had not been used to caricature and other Jews during the centuries leading up to these events. Biblical interpreters saw in the Gospels and the Pauline Letters the ammunition they needed for their war. If we ignore this fact, we risk repeating it. We need to be responsible interpreters, relentlessly aware of the fact that our articles and monographs have the power to change a two-thousand-year old pattern. We have the power of releasing NT texts from the interpretative prisons they have been trapped in from the time of the Church Fathers. It will be an uphill battle, not least due to the alarming number of scholars who have during the decades attached their sense of self-worth to anti-Jewish exegesis, but so is everything worthwhile. The climb may be steep, but there is an oasis of redemption waiting at the top, redemption for the authors whose texts we turned into weapons.

JJMJS Graces Us With a Second Issue!

The second issue of the “Journal of the Jesus Movement in its Jewish Setting” is out. Brace yourselves for yet another amazing read – prepare to have your horizons widened! The issue is jam-packed with interesting reads, an academic goody-bag. As someone who has recently become increasingly intrigued by the vortex that is modern Pauline studies, this issue became a little like a gateway to the Paul within Judaism context. I especially enjoyed Ralph Korner’s article on the ekklesia as a Jewish synagogue term (which left me with the distinct feeling that universities should focus more of their teaching on institutions, especially in our field).

Click here to explore and be challenged!

Subservient Wife or Cozy Ecclesiology?

A few days ago I did something outside my comfort zone: I led a Bible study on Ephesians 5 in a Christian student association. Those who know me well enough will note that almost every word in the preceding sentence is like a little gust of wind propelling me farther and farther from my safe little zone of convenience and comfort. First, I’m one of those individuals that people avidly fear inviting to Bible Study groups – that annoying girl who just can’t stop herself from pointing out that “there’s like a -10% chance that Pilate’s wife’s dream was a historical event rather than a theological point” or the eternal reminder to “choose silence over harmonization”. Second, I’m a Gospel Girl through and through; the letters have always been more of a Sunday event for me than an everyday occurrence. Third, I’ve never really been part of a Christian association: when I go out (as in exit my own little bubble) I like to kill two birds with one stone and learn something new at the same time, so I’m often drawn to events and associations catered to people who are different from me in some way, or are part of a group I don’t know that much about (like my brief stints with the Muslim Student Association and Community Garden Club at my Highschool or my faithful attendance to the various lecture series hosted by Hamilton’s Jewish Association). The result of this is that I sometimes find myself in possession of more knowledge about other traditions and faiths (and gardening techniques) than my own. Perhaps this is one of the reasons I’ve become more and more drawn to various Christian settings since I started university (make no mistake though: the restless nature of my relationship with associations perseveres: I think I visited every Christian denomination in Uppsala before I finally set foot in a Church of my own tradition).

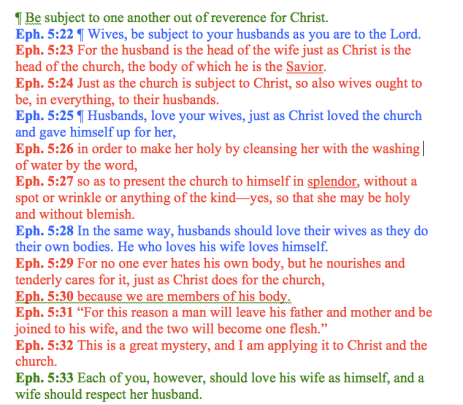

But enough of this introspection, let’s get down to the good stuff: what did I learn? Answer: our attitude to the Bible can either unite or divide us. To explain: I was determined to lead the Bible study on Eph 5 because I was keen that 5:21-33 (on the “Christian family”, as its labeled, faultily, in most Bibles) should be given the space for theological and exegetical reflection it deserves (and I was obsessed with the text for a good two months last semester, so I felt that I could cater to this aim). What’s most fascinating about this text is how much it changes when put under the scrutiny of a rhetorical analysis. If read quickly, one would categorize it as the first section of a “family theme” stretching into chapter 6, but the more I read the text from the perspective of literary analysis, the more I felt that it should rather be seen as the conclusion – the summa summarum – of chapter 5. Permit me to expand the explanation: 5:1-5 can be epitethed “Imitatio” (it explains that we should imitate God), 5:6-14 can be renamed “Beware the Emptiness” (since it explains how empty words lead to actions of darkness, revealed only by the light of Christ), 5:15-20 can be re-labelled “Lonely Planet: Guide to Christ” (since it’s like a guide of how we should live once Christ’s light has shown us the difference between good and evil deeds). This leads (as is demonstrated below) to the not-so-un-controversial christening of 5:21-33 to “Christ gets cozy with his ἐκκλησία”, instead of the frankly more triste “Man Heads, Purifies, and Dies For Subservient, Respectful Wife”. How do I have the chutzpah to suggest such a name shift? Have I brought some show-and-tell artifacts with me to back up my gutsy claims? Indeed I have. Exhibit A:

Legend:

Green: universal statement/rule

Blue: social implications

Red: Theological justifications.

Before I delve into this colourful little affair I have to come clean about something. The idea for this colour-coated interpretative key was derived from a lovely little article I read on 1 Cor 7:17-24 (comment below if you want a link to the PDF), in which the scholar categorized the different types of statements Paul makes, in order to ascertain what the main message – or the universal, theologically normative statement – of the passage was. I dubbed this delightful method statement typology and proceeded to apply it shamelessly to as many Pauline texts as I could possibly get my hands on, until I hit gold with Eph 5:21-33. The typology above is self-explanatory, but one thing should be noted: I am not oblivious to the fact that vv. 21 and 33 are not a perfect match in the chiastic sense, but then again, this is not a chiasm, simply a categorization of the significance of Paul’s statements, and I think both the first and last sentence were written as universal rules. What we see when we look at the typology is that the theological justifications (red) do not concern marriage so much as they concern Christ’s relationship to his ἐκκλησία. In particular, vv.26-27 stick out as two ugly sore thumbs when compared to Paul’s other statements about marriage (ex. 1 Cor 7), but fit snugly and neatly into the framework of Paul’s ecclesiology. Thus, my conclusion was that this passage is the summa summarum of chapter 5: because Christ and the ἐκκλησία are united in a marriage of sorts, each member of the congregation lives in such intimate proximity to that which is holy – the presence of God – that it is of the utmost importance for everyone to live as ἅγιος ( 5:3) – consecrated (with all the purity implications this word brings with it), in order to ensure that the presence (kavod) of God continues to dwell amongst them. Thus, in the larger statement-typological scheme of the chapter, vv.21-33 represents the theological (-ecclesiological) justification for the guidelines and rules presented in vv.1-20 (these rules are, of course, intermingled with theological justifications on a smaller scale).

Ergo, when we read vv.21-33 as part of the “family scheme” of Ch. 6 rather than as the theological justification for the rules and guidelines outlined in vv.1-20, we risk loosing the full rhetorical beauty of Paul’s argument. Without vv.21-33, the reader will not understand that the reason Paul sets such high moral standards for the congregation is because the ἐκκλησία, much like the Jerusalem Temple, is a place where God’s presence (in the form of Christ) mixes and mingles freely with the human. But in order for this holy blender to function, the congregation has to be pure (because, according to Jewish temple theology, relevant as always, the holy [set apart] and the impure cannot coexist). The metaphor of marriage to describe this relationship is a genius move for which Paul deserves much kudos: he uses contemporary ideals and constructs in order to explain a universal and normative concept. The metaphor also fits like a hand in a custom-sown glove with the classical Jewish way of describing the covenant between God and Israel – the very reason Israel needs to follow the Law (or should I say guidelines and rules) in the first place (see Hosea, Song of Songs’ traditional interpretation etc.). If we attempt to contextualize all this, I would posit that the focus in the Church today should perhaps be shifted away from the social construct and instead be centred on the universal concept Paul was in fact attempting to explain.

The point that I began making about three paragraphs ago is this: although this interpretation of the text may seem very academic and not very Christian (better word: confessional), the Bible study went unexpectedly well. Turns out that as long as you are serious about your interpretation and you don’t dismiss the Bible’s every detail as “contextual with no chance of universal”, you can have extremely rewarding conversations with people from all different kinds of denominations. Ergo, if we are serious about ecumenical and inter-religious dialogue, the answer is not to trivialize our differences, but rather to take them seriously and discuss them in an engaged, respectful, and reflected manner.

Disclaimer: I am aware that there is an ongoing discussion as to whether the historical Paul was in fact the author of Ephesians. My usage of his name in this entry should not be taken as proof that I side with those who believe in Pauline authorship. It is simply a result of my not knowing enough about the debate to make a reflected decision, and thus choosing to use the name that the text itself identifies as its author. Whether this “Paul” (Eph 1:1) is in fact the historical Paul or someone else writing in his name is a different question, one which I am not equipped to even take a guess at here. In addition, I also want to make it clear that I don’t mean to posit here that Eph. 5:21-33 is unconnected to the first section of Ch.6 – because it is – but I think the implications and meaning of the text changes dramatically depending on which emphasis you choose to read it with.

Do We Read The Bible Through Rose-Shaded Glasses?

Last week I attended a seminar which was a bit out of my usual academic range: a joint venture between the faculty of Semitic Languages and Hebrew Bible (otherwise known as “Old Testament”, although I have to admit that I’m 100% ready retire that term for good in academia). It was an interesting experience, and I learned hordes of peculiar facts that I never would have even gotten close to learning if I hadn’t gone (for example, I am now able to distinguish between three different types of deer based on the Hebrew word used to describe them in the HB, something which I’m actually childishly excited about). During the seminar, we examined different usages of the term “ayal” or “ayelet” in order to determine exactly which animal the term refers to (deer, ram, gazelle etc). Ps 42 was used as a point of departure, something which propelled my mind in a multitude of directions (as psalters are bound to). One of the professors said that the literary function of the word “ayal” was not to specify which sort of animal it was, but rather to use the animal as a comparative tool, so as to highlight certain qualities or attributes. I agreed that this was the word’s function, and proceeded to attempt to establish exactly which qualities or attributes the animal was meant to emphasize or highlight in the text at hand:

As a deer (אַיִל) longs for flowing streams, so my soul longs for you, O God. My soul thirsts for God, for the living God. When shall I come and behold the face of God? My tears have been my food day and night while people say to me continually, “Where is your God?” These things I remember, as I pour out my soul: how I went with the throng, and led them in procession to the house of God, with glad shouts and songs of thanksgiving, a multitude keeping festival.

Ps. 42:1-4

Two answers presented themselves to me: either a) אַיִל is used to highlight the feeling of an animal low down on the food chain searching for life-giving water or b) אַיִל is used as part of a larger imagery scheme. Option a) is pretty much self-explanatory, and who knows, it might even be the better of the two, but my mind couldn’t just let option b) slip away unnoticed. When I looked up ayal in BDB Abridged Hebrew Dictionary (courtesy of Accordance, as so much is nowadays), the word was translated as “ram”, and the explanation dealt largely with cultic usages of the animal: the sacrifices of Abraham, Balaam, Aaron and his sons, as well as in shelamim and Passover sacrifices and various consecration rituals. At first I dismissed this as irrelevant information, in favour of option a), especially since the definition is ayal also includes mention of how it is used as a simile for leaping/skipping behaviour. But upon closer inspection, it occurred to me that the verses actually include a number of other cultic images. Water can, albeit perhaps rather hazily, be linked to the temple via Ezekiel’s visions, ‘beholding the face of God’ was a temple-related activity, and, of course, we have the explicit mention of the “house of God” and “festivals” in the latter verses. Thus, I would posit that ayal, as a common sacrificial animal, was used as part of a larger temple-based imagery scheme. The aim of the psalmist is to express a desire to come closer to God, for God to draw near to him/her. The natural setting for such divine closeness during this time period was, in fact, the temple, and thus it is, to my mind at least, not unthinkable that an author wishing to express a desire to draw nearer to God in a concrete way would situate this desire within the narrative framework of cult and temple.

This little tangent lead me down a disconcerting thought-path. Regardless of whether my musings about this particular psalm are justified or not, how often do we miss the meaning of a text because our minds are not perceptive enough to the more subtle examples of temple imagery? Take Ps. 69:22-25 as an example. Here, the psalmist writes about his/her enemies, that their “table (שֻׁלְחָן)” should be a “trap and a snare for their allies (shelomim; from the root שָׁלוֹם)”. Many commentaries state that this “table” is related to v.21: “they gave me poison for food, and for my thirst they gave me vinegar to drink” (thus: the psalmist wishes his/her enemies and their allies to be poisoned). I have my (perhaps unjustified albeit still strong) doubts about this hypothesis. I would rather see v. 22 as the beginning of a new section. After naming the various injustices the psalmist has been subjected to, s/he now turns their attention to the misfortune s/he in turn wishes his/her enemies to fall victim to. These misfortunes are not necessarily related to the specific injustices the psalmist as fallen victim to. In fact, I believe them to be much, much worse. Shulkhan (table) can also be used to describe an altar, and there are several scholars (as well as a Targum) who wish to connect the word shelomin to the shelamim sacrifices. If these two things are emphasized, the summa summarum of v. 22 is that the psalmist wishes his/her enemies to loose their divine connection and thus all their fortune – if their altars become a trap for them and a snare for their sacrifices, they can no longer uphold a relationship to the divine. To my mind, this interpretation is a nice narrative fit – the psalmist juxtaposes his/her desire for God to draw nearer to him/her (vv. 17-18) with the desire for God to remove God’s presence from the camp of her/her enemies (v. 25).

These thoughts left me with the question: how can I apply this in my studies? I decided that the next time I am indulging in a bit of Bible reading, in particular NT reading, I would try to read the text from a perspective of temple and cult, just to see if the meaning of the text could be altered. It’s been an exciting experiment so far, one which I think I will continue with for a while! Matthean texts in particular take on a life of their own when you read them from a perspective of temple and cult, especially the Sermon on the Mount (I won’t say how – that’s for you to discover!), but I’m really enjoying reading John from a temple-oriented perspective as well. Is there any greater feeling than the realization that a text has been severed from the constraints of your own presuppositions and biases, if only for a moment? We have a regrettable tendency to colonize our texts with our own wants and needs – it’s high time we took a hint from postcolonial exegetes and set them free!

PS. I don’t usually keep my posts as gender neutral as this one when speaking of Biblical literature (because, let’s be honest, the authors were in all historical likelihood men, so I don’t see the point in pretending this unfortunate historical statistic doesn’t exist), but in the spirit of setting the texts free from my own constraints, I thought it would be fun to experiment with the thought that the psalmist could be either male or female, and if marking this in my analysis would have an affect on my own perception of the text. I have to admit that I enjoyed the affect it had – textually admitting that the author of a Biblical text could be either male or female actually opened it up for me, made me feel closer to the psalmist and more connected to the narrative. I’m still not sure how historically productive it was, but not everything has to be done from a functional perspective!

Some Musings on Rituals and Tradition Transmission

Scholars have been turning and twisting in angst at night for centuries trying to figure out exactly what happened in that relatively tiny gap between Jesus’ actual ministry and the writing down of the letters and the gospels about him. A tiny gap that turns into a gaping black abyss of a hole if you stare at it long enough – like Chinese water-dripping torture. I’ve just recently experienced a surge of interest in this period myself, and I’m finding it increasingly difficult to traverse the vast and littered battlefield of different theories and hypotheses. Since I am a student at Uppsala University in Sweden, I felt morally obligated to begin my odyssey with “Memory and Manuscript: Oral Tradition and Written Transmission in Rabbinic Judaism and Early Christianity” by the former Uppsala-educated and Lund-based professor of NT, Birger Gerhardsson. I’m only a couple of pages in, but I can already feel that the book will become a guide of sorts – the Lonely Planet to the world of tradition transmission – for me. Although it is important to remember that Gerhardsson wrote the book in the 60’s, my opinion so far is that, although I might not agree with all the specifics (like his, for me unrealistic, faith in Josephus’ trustworthiness and his approach to the dating of the Rabbinic material he makes use of), his methodological discussions are very interesting, and they propel the mind forwards, to new ideas – which is all one can, and perhaps should, ask of academic literature.

But, I don’t want to make this an entry about “Memory and Manuscript” (although I just have to make a note of how much I appreciate alliterated titles! This one has to be one of the more delightful ones I’ve come across – short, sweet, succinct!). Rather, while reading the first chapter, something occurred to me which I felt I needed to expand upon. The idea of tradition transmission is an interesting one – but is an analysis of literature really the way to go about it? In a context were the majority of individuals were illiterate, are we misleading ourselves by placing too heavy of an emphasis on the literary relationships between the early Christ-believing texts, in some sort of (to me seemingly) banal attempt to extract “red strings” of tradition from them, strings which we hope will somehow lead us back to that hilly Galilean landscape where the words were first uttered? Hansel and Gretel have not wandered into the Gospels before us, leaving breadcrumbs for us to follow that lead us straight to the words of Jesus.

My uncle is a reverend, and he once told my family about a curious phenomenon in one of his old congregations. The actual church building they used was old, pre-dating the Reformation, like many of Sweden’s churches. When Gustaf Vasa imposed Lutheranism on his kingdom, many of these churches were white-washed on the inside, so as to cover up the elaborate, Catholic church art they often boasted. In his particular congregation, there was an old tradition to touch a specific part of the wall just inside the entrance of the building upon entering the church. In connection with the growth of the High Church movement and a general desire to explore the roots of the Church, many of these white-washed churches were restored to their original, more colourful forms. Lo, and behold, when the white paint was chipped away from the interior of my uncle’s church, what do you think they found under the spot which hundreds of church-goers had touched in reverence throughout the centuries without remembering why? A painted icon of the Virgin Mary. What can we deduce from this (apart from the fact that it’s like a commercial for the High Church movement)? That rituals last longer than ideas. The church-goers of my uncle’s former church had forgotten why their parents used to touch that specific spot on the wall – they did it out of habit, ritualized habit – rather than out of some sort of Marian theological convictions. Yet, those first church-goers who began touching the wall, did it out of respect and reverence for a religious figure to which they were no longer allowed to publically display devotion. Rituals outlive theological ideas. Ergo, it is my humble opinion that it would perhaps be more interesting to try to trace rituals rather than literary dependence in the gospels. Admittedly one could probably use literary dependence to trace rituals, but the point I want to make is that it would be interesting if the point of the analysis was to identity traces of early Christ-believing rituals in the Gospels and Paul, rather than trying to identify exactly how certain Jesus Sayings are related to each other from a literary standpoint. Of course, if one views the transmission of tradition as a ritual (which I think one ought to), these Jesus Sayings are still afforded an important role in the investigation.

Although I realize that this post is of a highly fragmentary nature academically, I nevertheless cannot stop myself from feeling that the most important aspect of historical research (for me at least) is to uncover the lives, habits, and convictions of the (ordinary) people behind the texts – the illiterate ‘masses’ who make up the backbone of any group, but who are rarely represented in our source material. Perhaps this feeling is based on a strange sense of displaced responsibility or some sort of Western-scholar-guilt, or perhaps it represents my ideologically-tainted conscience flaring up. Either way, when we place too heavy an emphasis on literary dependence theories and the like, I cannot help but feel that we risk banishing the vast majority of ancient Jesus Followers into the margins of history, when they in reality deserve a place of honour – a place that is perhaps more easily awarded them if we place a greater emphasis on ritual analysis and tradition transmission as performance.

Blinded By Bultmann?

“It is in truth far from easy to say how an eschatological prophet who sees the end of the world approaching, who senses the arrival of the Kingdom of God, and who accordingly pronounces blessed those of his contemporaries who are prepared for it (Matt 13:16-17, 5:3-9, 6:5-6 etc.) – to say how such a person could argue over questions of the Law and turn off epigrammatic proverbs like a Jewish rabbi (since to practically all the moral directions of Jesus there are parallels and related words of the Jewish rabbis), in words which contain simply no hint of eschatological tension (e.g. Matt 6:19-21, 25:34, 7:1, 2, 7, Luke 14:7-11, Mark 2:27, 4:21).”

Rudolf Bultmann, “Form Criticism: Two Essays on New Testament Research”(1934).

This sentence accosted me as I attempted to delve into my long-awaited (and, let’s face it, mandatory) Bultmann-reading. At first glance, I dismissed it as a product of Bultmann’s zeitgeist. But as I continued reading I kept coming back to it in my mind. Is this really just a product of his zeitgeist, or is it also a product of our zeitgeist? Does NT research still hold this to be true, albeit (usually, optimally) under the surface? I don’t think many serious scholars today would suggest that Matt 25 is not an eschatological text, but are there examples of how this (false) juxtaposition between moral sayings and eschatological beliefs still rears its ugly head, perhaps disguised in a little something we like to call ‘Q’?

I want to begin this analysis by pointing out the obvious: Bultmann was extremely sharp. Even though most NT scholars have perforated the power dynamics of form criticism (in theory at least), I think we can all agree that its giver-of-birth was a man with a bright and innovative mind. Right, now that the obligatory disclaimer has been taken care of, let’s move on to the juicer part of the argument: the place of eschatology in modern NT scholarship, and the burden of “moral teaching” that Bultmann has loaded onto our collective backs.

Let’s start by assaulting the Lutherans (since I categorize myself as a follower of Luther in the most general sense of that term [the one thing Bultmann and I have in common], my conscience finds it easier to start the rampage closer to home). Lutherans have a specific way of reading the Old Testament and dealing with all the disconcerting theological complications it brings forth. I like to call it the “Quick-n-Easy Ethical Fix”, a model influenced by Bultmann and his clique. The approach consists of categorizing the precepts and laws in the OT into two categories: cultic and ethical. The ethical rules are to be followed; the cultic rules are to be ignored. Quick and easy. Or is it? Are we really capable of distinguishing between the ethical and cultic laws in the Bible (yes, the Bible as a whole: the NT also contains a number of cultic rules [see Matt 5:22-24], which is enough to confuse one to distraction if one is too strict in one’s Lutheran appropriation of the Bible)? Is the distinction between cult and ethics valid at all?

If we take a closer look at Jeremiah 7, a different image begins to form. The passage begins with a reference to the Temple, thus setting the thematic stage as a cultic one. In 7:6-7, the speaker, God, says that He will not continue to dwell in the temple unless the people do not cease oppressing the immigrant, the orphan, and the widow; shedding innocent blood, and worshipping other gods. This is, according to my mind, one of the best examples of how mingled and messy the supposed “borders” between ethics and cult is: what we categorize as moral guidelines (not oppressing the immigrant, orphan, or widow; not shedding innocent blood) is intimately connected to cultic matters (God dwelling in the temple), making it very difficult for us to distinguish clearly between them. Of course, in Jer 7 it is much easier for us to tell the difference between “ethics” and “cult”, since the ethical guidelines are some of the most celebrated rules in Judeo-Christian tradition. But what about other texts, where the contextual veil is harder to lift, like Ps. 51:16-19? Matt 5:22-24 is another such example. The majority of preachers (and perhaps many scholars as well) would tell their flock that this is a text about the importance of reconciling with your brother or sister. They wouldn’t be wrong per say, but it’s also a text about how to make offerings without tainting the sacrifices with moral impurity, something which often gets left out of the discussion. The pattern in Jer 7, Ps. 51, and Matt 5 is the same: “moral” behaviour is linked to the purity/impurity of God’s dwelling place, in the same way that ritual purity usually is. The existence of moral purity and its cultic connections makes it difficult to draw a clear line between ethics and cult – the line quickly turns into a blurry smudge. Perhaps what we today label as “ethics” and “cult” were once one and the same thing: meshed together, two strings in the same Biblical tapestry.

You may ask (rightfully) what all this has to do with Bultmann and eschatology. Allow me to humbly attempt to tie the strings into a bow. Eschatology and cult in the Gospels are like twins borne of the same womb. In Mark 13 with synoptic parallels, known as the Little Apocalypse, Jesus ties the destruction of the temple (cult) to the End of the Ages (eschatology). Indeed, the “discussion of Law” that Bultmann mentions in the quotation above often dealt with matters of purity (Mark 7, Matt 5:22-24; 15 etc.), which means that regardless of whether we think he was for or against it as a concept, Jesus still taught about cultic matters. Thus, since the part of the Mosaic Law dealing with cult is intimately related to the eschatological vision of Jesus, and since there is no difference between cult and ethics, one should perhaps also problematize the separation of eschatology and ethics in the NT. By carving what he referred to as ethics out of the eschatological entity of the Gospels with his exegetical scalpel – dripping with the poison of early twentieth century zeitgeist – Bultmann invented a new category (not to mention a bleeding mess of an interpretative wound). This new, neat, comfortable category fit so well with the beliefs of his time that it settled in like a relative on a visit. But the visit was prolonged and prolonged, until Aunty Ethics became a permanent resident. And now we take her for granted, like an old, comfortable couch that we stash in the corner of our living room even though it doesn’t fit with the rest of the décor, just because we don’t want to go through the hassle of lifting it out the door. It’s high time to re-decorate.

When we accept what Bultmann says about ethics (subconsciously or not), we accept a worldview where the role of Jesus is stripped of its eschatological and cultic function, where cult and ethics become opponents in some bizarre puppet show. But, as Schweitzer pointed out (to pit Bultmann against a contemporary), the historical Jesus becomes void of meaning when his mission is de-eschatologized. The Gospels all place the heaviest focus on the Passion Narrative – it is the climax of the story, the culmination of the narrative. Thus, Jesus’ teaching needs to be in coherence with his death, since everything is leading up to it. Why would the Romans execute an ethical teacher preaching love and justice for all? They wouldn’t. Who they would execute, on the other hand, is a wandering Galilean prophet who preached charismatically about the End of the Ages, the supremacy of the God of Israel over all other gods (read emperors), and the religio-political restoration of a colonized people.

Thus, most modern scholarship has in large parts established that Jesus was an eschatological messianic figure. Ergo, according to the line of argumentation I’ve been attempting to follow, Jesus’ eschatological teaching must also contain cultic aspects (which we saw when we looked at Matt 5).Thus, since there’s no clear line between cult and “ethics” in the Bible, Jesus’ teaching cannot be classified as ethical. Thus, Bultmann’s argument above that Jesus’ eschatological statements should be in some way contradictory to Law discussions is unsustainable and deeply problematic. Much of the Law is connected to cultic matters: all the purity laws (moral and ritual), laws regulating temple practices, taking care of immigrants and widows (because otherwise the Land will “vomit you out” – the Land being tied to the Temple), etc. etc. If we strip discussions of the Law from their cultic and eschatological function, we risk loosing the meaning of Jesus’ teaching.

In the examples that Bultmann lists at the end of the quotation, we can see how confused the picture gets when one juxtaposes the invented category “ethics” with eschatology. The Matthean examples are particularly jaw dropping. It is difficult to wrap one’s mind around how the following: “then the king will say to those at his right hand, ‘Come, you that are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world’” could be interpreted as an antithesis to eschatology. As a dedicated opponent of ‘Q’, I can’t help but note that this is the tradition one falls into when one accepts theories such as the Two Source Hypothesis, which is based on the assumption that the oldest and most authentic manuscript about Jesus is an almost purely ethical text – not eschatological, not cultic, not enough of a deviation from Bultmann to put my mind at ease.

Is the Shortest Way to Jesus Really the Best Way?

A few weeks ago, I caught myself reading Helmut Koester’s important book “Anicent Christian Gospels” (1990). After having read the Gospel of Philip, I was confused enough (both academically and as a Christian) to feel compelled to surround myself with literature concerning ‘apocryphal’ gospels and the like. Although this reaction didn’t necessarily ease my confusion (it only gets worse after a certain point [for me that point was differentiating between different forms of Gnosticism without enough source material, but for you it might be the intricate relationship between the Gospel of Thomas and the different layers of Q]), it did wake me up to some harsh exegetical realities.

It seems to me that the unspoken rule behind the majority of theories surrounding (suffocating?) the relationship between the canonical Gospels, “Q”, and Thomas is that the shortest text is the most original. As if ancient authors were incapable of summarizing, as if they had some sort of innate need to expand on everything they copied – as if the first person to write about an event or a Jesus saying was always the most succinct. I don’t know about you, but if I witnessed a crucified guy stepping out of a grave dressed as a gardener (there must have been some reason Mary confused her ‘Rabbouni’ with a carer of plants) I would find it hard to organize my thoughts to the point where I could produce a succinct theological statement about it. I’m not saying that any of the texts in question were written by an eye-witness (I don’t want to be disowned by the academic community), I’m trying to use a hyperbolic example to illustrate that the assumption that the shortest text is the oldest might be what some would refer to as a logical fallacy. In many cases it seems that theological statements tend to get more stylized and succinct as time passes, when the need for them to be institutionalized and cohesion-producing emerges.

Reading Koester’s arguments concerning the relationship between the canonical Gospels, “Q”, and Thomas was a uniquely frustrating experience for me (probably because I feel so strongly about “Q”). It seemed to me that the main argument supporting the claim that “Q”, a text which we have not found and which might not even be entirely textual (yes, the differentiation between textual and oral Q is a real thing), was more faithfully copied by Luke than by Matthew, is that Luke is often more succinct than Matthew. The same logic is applied when comparing Thomas to the canonical Gospels (something which is somehow even more frustrating than the above-mentioned). Back to Luke and Matthew: the Sermon on the Mount (Plain) is often used as an example, and it’s easy to see why. It looks as though Matthew expands very evenly on the Lukan version. But, I repeat my earlier musing: could it not just as well be the case that Luke is very evenly summarizing Matthew’s version? Just for fun, I decided to go through my lovely little book of Gospel Parallels (a godsend on boring train rides, even though it does tend to produce some perplexed stares from fellow travellers) to see if there were any examples of the reverse. Turns out I found one on the very first page I opened. If one compares Matt 6:22-23 with Luke 11:34-36, it seems to me that Luke is very clearly expanding on and explaining what exactly Matt means when he (excuse the generic masculine) writes “if then the light inside you is darkness, how great is the darkness”. Thus, even if I, by some nineteenth-century liberalistic miracle (oxymoron intended), decided to accept the theory that the shortest version is the oldest, I would still be left with the disconcerting realization that Luke sometimes expands on Matt anyway. The shortest way to Jesus isn’t always as straight as it sometimes appears in scholarly literature; there are a lot of confusing twists and turns on the way even here.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not saying that the longest version necessarily has to be the oldest. I’m just saying that the assumption that the shortest version is the oldest is an empty assumption – empty of force and function, unrelated to how things tend to work outside the safe embrace of a university office.

Why Radford-Reuther’s Jesus Reconstruction Needs a Reality Check

After reading Rosemary Radford-Reuther’s book “Women and Redemption”, I feel the need to raise some critical thoughts concerning her Jesus reconstructions, based on the following question:

Who is the Jesus Radford Reuther reconstructs? Who does she reconstruct him for?

He is a Lukan Jesus. Radford Reuther bases almost all of her assertions about Jesus on the Gospel of Luke. The canon about Jesus is diverse, and all its nooks and crannies should be taken into consideration, especially from an academic standpoint, where the scholar is not supposed to value some passages over others (which theologians are permitted to do). Her Jesus came only for the poor and the marginalized, and his message of deliverance to them is not an apocalyptic one (here she disregards Mark 13 with synoptic parallels), rather it is one of little to no eschatology/apocalyptic expectation, a purely Lukan theology (as interpreted by nineteenth century German theologians…I would venture to say that Lukan theology is eschatological by nature, just like the other Gospels). She also focuses on Luke’s inclusion and focus on women – for example, in Matthew the nativity revolves around Joseph, but Radford Reuther chooses to place all the emphasis on Mary, thus creating a biased image of the Jesus narrative.

He is an anti-Jewish Jesus. Radford Reuther’s Jesus does away with all the Jewish purity laws (here it should be noted that she fails to make the very important distinction between moral and ritual purity, rather she clumps them both together). This too leans towards the Lukan, and is an outright negation of the Matthean Jesus, who seems very concerned with both purity and the Law as a whole (see Matt 5:17-24). The same can be said of the Johannine Jesus, who in his conversation with the Samaritan woman states that the Jews worship God on the correct mountain, thus affirming the legitimacy of the Temple function, which in many ways depends on the purity laws. The Markan Jesus too observes some sort of purity when he says that only that which comes out can cause impurity (a direct reference to the purity laws in Leviticus). Radford Reuther’s (mis)understanding of the Jewish purity laws as a means of oppression is both borderline anti-Jewish and leads her down a road of great exegetical peril. In addition, Radford Reuther creates a dichotomous relationship between Jesus and Jewish patriarchal culture. Amy-Jill Levine successfully argues against this misconception in her article in the Jewish Annotated NRSV (definitely worth checking out!).

He is a modern, Western Jesus. Radford Reuther’s assertion that Jesus may have been illegitimate is highly anachronistic, and does not take into consideration the laws about sexual immorality at the time, nor the understanding about God’s relationship to his “Anointed”. In addition, her assertion that he had little to no eschatology/apocalyptic expectations and that he created an “egalitarian community of equals” is not historically plausible. Contextually, that would make Jesus too different from his surroundings to make sense from a historical, academic standpoint. So perhaps what Radford Reuther is doing here is actually some highly anachronistic theological musing. But if this was theology, she has created a Jesus who does not fit into any Christian doctrinal frame, making it a problematic theology since it doesn’t take any other perspectives into consideration and makes no reference to Christian faith or traditions.

Jesus: A Jewish-yet-not-too-Jewish Road-tripping Galilean?

A couple of months ago I attended a tutorial at the theological faculty. One of the professors was complaining about the state of historical Jesus research, pointing out that everyone seems to be saying the same thing: “Jesus was Jewish…but he didn’t follow the Jewish Law…he wasn’t really like other Jewish leaders during this time…he didn’t respect the Sabbath…and obviously he didn’t keep the purity Laws”. So in essence, everyone starts with a hypothesis and then unwittingly argue against it while they’re trying to argue for it. Everyone says that they’re part of the “new perspective”, but in reality, the consequences of what they say aren’t that different from Käsemann (and his criteria of anachronistic cultural colonialism). I wholeheartedly agree with my professor: is it really good research if everyone is simultaneously arguing for and against the same thing?

To my mind, the root of the problem is this: scholars often want to distill Jesus down to something they can agree with themselves (to paraphrase Sanders). They want a Jewish-but-not-too-Jewish Jesus, someone who eases their Christian guilt by being Jewish, but who isn’t so Jewish that he becomes alien to them (classic example of creating facts to suit theories). The problem (or, rather, one of the problems) with this is that “Jewishness” is not a comparative concept. It’s a religio-ethnic category which you either are or are not a part of: you can’t be semi-Jewish, pseudo-Jewish, “diet-Jewish” or “Jewish-light”. Is your mother Jewish? If the answer is yes, then so are you. Was Jesus’ mother Jewish (and for those of you out there who don’t believe that second temple Jews traced ethnicity via their mothers: read father [if human, descendant of a Jewish king, if divine, son of a Jewish God])? Answer: yes, problem: solved. Once you have established this relatively straight-forward reality, you have to deal with its consequences. A second temple Jewish man who wanders around preaching about the coming of the Kingdom like a proper Old Testament prophet but who doesn’t follow the Jewish Law is an oxymoron. It’s not a religio-cultural category that existed during this time – when scholars try to get all Bultmann-y on Jesus, they are attempting to create a “Diet-Jesus”, someone they can agree with, someone who will agree with them, distilling a religio-historical phenomenon down to something that can be easily swallowed by our modern mindset.

This is deeply problematic from both an academic and a religious perspective. Academically, it’s highly anachronistic – it’s bad methodology (the root of all evil). Religiously, it creates a lense through which we distort our holy scripture. We want Jesus to be a certain way, and so we ignore all the indications in the text that point to something else. That Jesus was a full-blown second temple Jew isn’t a faith problem: I would be more worried if he didn’t follow the Jewish Law, because then he wouldn’t be in sync with the prophecies he’s fulfilling – the continuity would be broken.

In conclusion, if you pick up the New Testament looking for a sugar-coated fairy tale about a nice Jewish-yet-not-too-Jewish man and his faithful friends road-tripping through Galilee, you’ve come to the wrong place. The New Testament is a book about a messiah, a prophet like Moses, who came to the world to announce the fast-approaching judgement; the final, eschatological judgement that would usher in the Kingdom of Heaven. In order to allow for the coming of this Kingdom, the messiah had to die a horribly gruesome death, only to rise again, clothed in morning’s young blush. There’s nothing cozy, nice, ethical (according to our modern definition), or un-Jewish about that.